Introduction Part 2: Models, All the Way Down

March 9, 2021

In part one of this introduction I put forward the idea that the predictions arising from mental models play an integral role in software development. Unlike that post which was intentionally formal, this one derives far more from introspection and observation. I want to use this relative freedom to share some musings.

Specifically I want to think about what these models might be made from, and given that, consider the dynamics which we experience when manipulating these thought-units.

More prosaically, I also want to introduce terminology (which I’ll flag as side-notes) which I hope will make subsequent posts on the experiences arising from all these comprehensible.

In order to speculate like this, I need to go bring in one more collection of concepts which, despite not appearing so at the time, have continued to resonate with me, and feel relevant for us here.

Back in 2016 I was trying to learn algebra. It was long overdue. It was also hard. Really hard. And once again, someone from the Java Posse Roundup came to my aid.

During a conversation about my travails (it probably took place in a queue for coffee) Todd mentioned a book by Barbara Oakley which he’d found useful: “A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science”.

I approached it with caution. I rarely have the cheek to say out loud how much I distain these “pop-Psychology” booksI have a real Psychology degree forchirstssakes!#$%^*!! , but I also frequently give them a try, and that’s what I did here, admitting to myself that anything which could give me even a toe-hold on the seemingly impossible cliff-face of mathematics would be of benefit.

It worked.

Before writing this post, I went back to the book and realised how much it contains. However I only want to bring out two elements here: the limited size of working memory, and a technique to tackle this called “chunking”.

Working memory first. It’s an enduring concept in cognitive psychology, having survived at least from the days of my degree1993-97 up to the present. It’s a concept of mental functioning usefully conceived of as a workbench. This workbench is where you do your conscious, front-of-mind thinking and decision-making. This “thinking” can function simply to keep information available, such as when you are trying to remember a phone number someone just told you, but it can also be more active and combinatorial, such as when you are trying to solve a maths problem.

It doesn’t seem like too big a leap to suggest that working memory is also the locus of active (thinking) work in software development. Whether that’s trying to piece elements together to create our solution, thinking to solve a problem, figuring out which language construct to use, or even remedying the surprise asrising from the aforementioned mis-match between expectation and sensed reality.

Now a key and inescapable fact about working memory is that it has a limited capacity. Oakley characterises it as being capable of containing a finite number of “chunks” as she terms them. She makes it clear that to have a “mind for numbers”And, by implication, a mind tuned for performing any complicated mental-manipulation task you need to be able to work effectively within this restricted space and clever chunk-fu is one way to do it. This “chunking” approach entails consciously, coherently and solidly forming shorthand chunk thought-units which can, while only taking up one of those precious chunk-slots, actually represent concepts of significant depth and detail.

Clearly when engaged in complex and conceptual brain work, “chunks” are incredibly valuable. But what are they exactly? Oakley offers us more detail:

“Chunks are pieces of information that are bound together through meaning. You can take the letters ‘p’, ‘o’ and ‘p’ and bind them together into one conceptual, easy-to-remember chunk, the word ‘pop’. Underneath that simple ‘pop’ chunk is a symphony of neurons that have learned to trill in tune with one another. The complex neural activity that ties together our simplifying abstract chunks of thought - wether those pertain to acronyms, ideas, or concepts - are the basis of much of science, literature, and art.”

(A Mind for Numbers, Oakley, pp.53)

She goes on:

“Chunking the information you deal with helps your brain run more efficiently. Once you chunk an idea or a concept, you don’t need to remember all the little, underlying details; you’ve got the main idea—the chunk—and that’s enough.”

(A Mind for Numbers, Oakey, pp.53-54)

I won’t labour the point any further. I hope all this feels super-familiar. Firstly as a description of daily development experience (which may or may not have a basis in neuropsychogical fact) but also secondly as a concept with exciting echoes and resonances for what I shared in the previous post, with regards to Friston’s ideas of mental models and their arising hypotheses.

Given all this, and given the fact that it frequently feels during development as if we are trying to wrestle a number of thought-elements within a finite mental space, how might we use the concepts I’ve lifted from Oakley to gain some insight?

The key question arises: “what might be the nature of the thought-units from which we build our mental-model castles?” I propose that these too are mental models; but more specific, more fundamental ones. My supposition is that, in order to fashion higher-order cloud castles, we manipulate smaller blocks of mental model, blocks which represent concepts we already have. It is, I propose, mental models all the way down. And it is these mental model blocks which are the things taking up the chunk-slots in working memory. Let me unpack this a little.

In part one of this introduction I conjectured that when I am developing software I am forming a model in my mind which I am continually conveying to the outside world in the form of code.

In performing this act of creativity I deploy the raw elements of what I know (or more precisely, what I expect) of my chosen programming language. I am using these pre-existing blocks of mental model, which comprise my idea of how the programming language and it’s constructs work — let’s call them the “substrate”This is your first terminology alert models — and from them construct my castle — let’s call that the “creation-solution”This is your second terminology alert model.

From this it quickly becomes clear that these concepts of “substrate” and “creation-solution” model are relative. From one perspective a mental model is the former (i.e. a LinkedList collection is to me a substrate model when I’m flat-mapping my way to a sum), but from another perspective it is the latterWe all know the core libraries we use for example are simply pre-formed building blocks created for us by others (i.e. a creation-solution model when I’m implementing a quantum-safe collections library). This does not only between developers. It also happens within the same individual, depending on the viewpoint we hold at any given point in time during development. For example, one moment I’m creating a component or a microservice, the next moment I’m calling it.

Given that the difference here is only one of perspective, and given my conjecture, both models can be expected to work inside our heads in exactly the same way: embodying a set of expectations of how the real-world (i.e. code) things they represent are structured and will function.

This fits brilliantly into Oakley’s chunks, because chunks are pieces of information formed from smaller-level pieces of information, bound together by meaning. Or put another way, mental models, comprising of smaller-level mental models. We, in short, construct mental models out of other mental models.

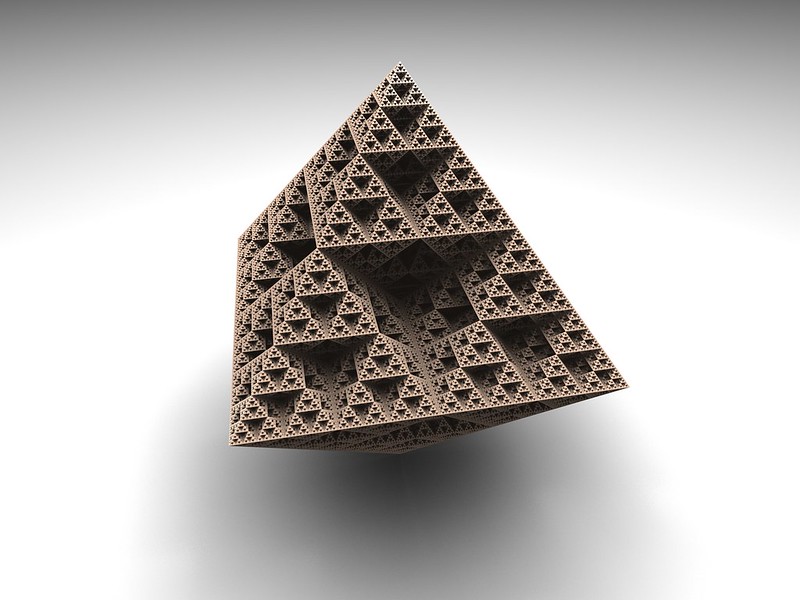

It’s models all the way down.

Before I close I must acknowledge the inevitable question: how do we work with (or against) these elements (and perhaps adopt other techniques from Oakley, knowingly or unknowningly) in our acts of development? Having thought about this for some time now, and having spoken to, and watched others working with code, I am convinced that this area is one where a great deal of individual difference lies. Consequently I believe this will be a fruitful one to investigate, compare / contrast, and discuss, in the main body of this effort. My first steps into this form the topic of my next post: “The Experience of Development - Chapter 1: The Fine Balance”

P.S. I’d love to know what you think about all this. If you have any thoughts or any other kind of feedback please reach out to me on Twitter. Thanks!